Billy Connolly

| Sir Billy Connolly CBE | |

|---|---|

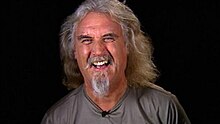

Connolly at the premiere of Brave in 2012 | |

| Birth name | William Connolly |

| Born | 24 November 1942 Anderston, Glasgow, Scotland |

| Medium |

|

| Years active | 1965–present |

| Genres | |

| Spouse |

|

| Children | 5 |

| Website | billyconnolly |

Sir William Connolly (born 24 November 1942) is a Scottish actor, musician, television presenter, artist and retired stand-up comedian. He is sometimes known by the Scots nickname the Big Yin ("the Big One").[1][2] Known for his idiosyncratic and often improvised observational comedy, frequently including strong language, Connolly has topped many UK polls as the greatest stand-up comedian of all time.[3][4][5][6] In 2022, he received the BAFTA Fellowship for lifetime achievement from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts.

Connolly's trade, in the early 1960s, was that of a welder (specifically a boilermaker) in the Glasgow shipyards, but he gave it up towards the end of the decade to pursue a career as a folk singer. He first sang in the folk rock band The Humblebums alongside Gerry Rafferty and Tam Harvey, with whom he stayed until 1971, before beginning singing as a solo artist. In the early 1970s, Connolly made the transition from folk singer with a comedic persona to fully fledged comedian, for which he became best known. In 1972, he made his theatrical debut, at the Cottage Theatre in Cumbernauld, with a revue called Connolly's Glasgow Flourish.[7] He also played the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. Also in 1972, Connolly's first solo album, Billy Connolly Live!, was produced, with a mixture of comedic songs and short monologues. In 1975, he reached No. 1 in the UK Singles Chart with "D.I.V.O.R.C.E."[8]

As an actor, Connolly has appeared in various films, including Water (1985), Indecent Proposal (1993), Pocahontas (1995), Muppet Treasure Island (1996), Mrs Brown (1997) (for which he was nominated for the BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role), The Boondock Saints (1999), The Last Samurai (2003), Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events (2004), The X-Files: I Want to Believe (2008), Brave (2012), and The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies (2014).

On his 75th birthday in 2017, three portraits of Connolly were made by leading artists Jack Vettriano, John Byrne, and Rachel Maclean. These were later turned into part of Glasgow's official mural trail. In October that year, he was knighted at Buckingham Palace by Prince William for services to entertainment and charity.

Connolly announced his retirement from comedy in 2018;[9] in the years since, he has established himself as an artist. In 2020, he unveiled the fifth release from his Born on a Rainy Day collection in London,[10] followed by another instalment later that year, and has subsequently issued another five collections. During the filming of the ITV documentary Billy Connolly: It's Been a Pleasure, he described how art had given him "a new lease of life".[11]

Early life

[edit]Connolly was born on 24 November 1942 at 69 Dover Street,[12] "on the linoleum, three floors up",[12][13] in Anderston, Glasgow. This section of Dover Street, between Breadalbane and Claremont streets, was demolished in the 1970s.[12] Connolly refers to this in his 1983 song "I Wish I Was in Glasgow" with the lines "I would take you there and show you but they've pulled the building down" and "they bulldozed it all to make a road". The flat had only two rooms: a kitchen-living room, with a recess where the children slept, and another room for their parents. The family bathed in the kitchen sink, and there was no hot water.[14]

Connolly was born to Catholic parents, William Connolly and Mary McLean, both of whom were of partly Irish descent.[15] In 1946, when he was four years old, Connolly's mother left her children while their father was serving as an engineer in the Royal Air Force in Burma.[14] "I've never felt abandoned by her," Connolly explained in 2009.[16] "My mother was a teenager. My father was in Burma, fighting a bloody war. The Germans were dropping all sorts of crap on the town. We lived at the docks, so that's where all the bombs were happening. She was a teenager with two kids in a slum. A guy comes along and says, 'I love you. Come with me.' Given the choice, I think I'd have gone with him. It looks as though it might all end next Wednesday, from where you're standing. I don't have an ounce of feelings that she abandoned me. She tried to survive."[16]

Connolly and his older sister, Florence (named after their maternal grandmother, and eighteen months his senior),[14][17] were cared for by his father's two sisters, Margaret and Mona Connolly, in their cramped tenement in Stewartville Street, Partick. "My aunts constantly told me I was stupid, which still affects me today pretty badly. It's just a belief that I'm not quite as good as anyone else. It gets worse as you get older. I'm a happy man now but I still have the scars of that."[7] Regarding his sister, Connolly has called her his "great defender".[16] "To this day," he explained in 2009,[16] "Guys say, 'God, your sister... We didn't dare beat you up – your sister was a nightmare'. She used to get after them."

In the mid-1960s, Flo was on holiday in Dunoon with her husband and two children. "My mother said, 'I saw Florence walking along, and I followed her.'"[16] "I said, 'Did you speak to her?' 'Oh, no, I didn't,' she said. I thought, 'Oh, my god. It's like being a ghost while you're still alive.' Walking behind your own child. Having a look. I couldn't bear that."[16]

The aunts resented the children for the fact that they had to sacrifice their young lives to look after them. It was Mona who was troubled the most by having to care for her niece and nephew. "It was very big of her to take on the responsibility, but having said that, I wish people wouldn't do that. I wish people wouldn't be very big for five minutes and rotten for twenty years. Just keep your 'big' and keep your 'rotten' and get out of my life, because, quite frankly, I would rather have gone to a children's home and be with a lot of other kids being treated the same. To this day, I'm still working on the things she did to me."[18][19]

Connolly credits one of John Bradshaw's publications with helping him deal with his past demons. "He reckons that if this trauma happened to you when you were five or six then, emotionally, that part of you remains five or six. And what you have to do is carry that five- or six-year-old around with you and try and emotionally help that other part of you. It sounds a bit airy-fairy, but I think he's something of a genius, Mr Bradshaw."[18]

His father returned from the war a stranger to his children shortly after the move to Partick. He never spoke to them about their mother's departure.[14] Connolly's biography, Billy, written by wife Pamela Stephenson, documented years of physical and sexual abuse by his father, which began when he was ten and lasted until he was about 15.[20] "Sometimes, when father hit me, I flew over the settee backwards in a sitting position. It was fabulous. Just like real flying, except you didn't get a cup of tea or a safety belt or anything."[14] In 1949, Mona gave birth to a son, Michael, by a "local man". He was presented as a brother to Billy and Flo, and nobody questioned it.[14]

Connolly's bedroom had double windows, which directly faced St Peter's Primary School across the street.[18] Now defunct, the school has been converted into living accommodation. "The school was very violent indeed. At first, in the infant school, the nuns were very violent. And then over here at St Peter's, they were just strapping you all the time. I had a psychopath in here, called McDonald — Miss McDonald. 'Big Rosie', they called her. There was a guy with glasses in my class and she called him 'four eyes', and she was a teacher!"[21]

At St. Peter's, Connolly decided that he wanted to make people laugh. "I can remember the moment in the school playground. I would have been 7 or 8. And I was sitting in a puddle and people were laughing. I had fallen in it and people found it funny. And it wasn't all that uncomfortable, so I stayed in it longer than I normally would because I really enjoyed the laughing. My life was very unhappy at the time, and laughter wasn't something I heard all the time, so it was a joy. And I realised quickly that if you can have an audience this way, life was rather pleasant."[18] While at St Peter's, Connolly joined a gang. His arch-enemy was Geordie Sinclair, who lived around the corner.[16]

Connolly was a Wolf Cub with the 141st Glasgow Scout Group. He revisits the site of one field trip, Auchengillan scout camp, during his World Tour of Scotland.[13] At age 12, Connolly decided he wanted to become a comedian but did not think that he fit the mould, feeling he needed to become more "windswept and interesting". Also at that age, he joined an organisation called The Children of Mary. The group would visit people and say the Rosary, with a statue of the Lady of Lourdes in a shoebox. "We were as welcome as haemorrhoids."[16] The group would all kneel around the statue and pray. "You could hear people hurrying prayers because there was a good television programme coming."[16]

In the 1950s, Glasgow's sandstone tenements fell out of favour with the planners, which resulted in new houses being built on the fields and farmlands in the outskirts of the city. Between the ages of fourteen and twenty, Connolly was brought up on a now-demolished council estate on Kinfauns Drive in the Drumchapel district of Glasgow, and would make the daily journey to St. Gerard's Secondary School (also now defunct) in Govan, on the southern side of the River Clyde. He rode the bus to Partick, crossed the water by ferry and walked to 80 Vicarfield Street.[2][13]

"Drumchapel is a housing estate just outside Glasgow. Well, it's in Glasgow, but just outside civilisation," he has joked.[13] "To be quite honest, I quite liked it when I lived there. When I moved to Drumchapel, I was fourteen and there was a bluebell wood there, and it was in great condition then — I don't think it's in quite so good condition now — but it was lovely then. We had rabbits and pheasants, and I really quite liked it. I just started to dislike it when I got older, into my teens and things. In my late teens, when I was stuck out there, it cost me a lot of money to go anyplace. It was a kind of cowboy town, but I liked that aspect of it, buying stuff out of vans, a ragman coming in a wee green van."[14]

Connolly revisited this tenement in Drumchapel during filming for The South Bank Show in 1992.[22] "It eventually started to pall. This dreadful atmosphere came about the place. It's like Siberia. And once you're out here, there's no getting out of it. You have to buy your way out, or some kind of talent has to take you out, or you have to be very bright and move away to university."[18]

Also at fourteen, Connolly started to become interested in music — mainly Jerry Lee Lewis and Chuck Berry. At fifteen, he left school with two engineering qualifications, one collected by mistake which belonged to a boy named Connell.[23]

Connolly was a year too young to work in the shipyards. Instead, he started working for John Smith's Bookshop, on St Vincent Street, delivering books on his bicycle. He became a delivery-van driver with Bilslands' Bakery until he was sixteen, when he was deemed overqualified (due to his J1 and J2 certificates) to become an engineer.[23] Instead, he worked as a boilermaker[24] at Alexander Stephen and Sons shipyard in Linthouse.[23]

"What an extraordinary feeling," Connolly said, upon returning to the site of the now-demolished shipyard in 1992.[18] "I spent a great deal of my life in here. From age 16 to... well, I started at 15. I started my apprenticeship at 16 and finished when I was 21. Stayed till I was 22, and moved along. I finished welding when I was 24. When I came here, as an apprentice, there was six ships being built, right where I'm standing. It was an extraordinary place. A hive of activity. Welders, caulkers, platers, burners, joiners, engineers, electricians. I learned how men talked to one another, and how merciless Glasgow humour can be. It has made an indelible mark on me."[18] His foreman was Sammy Boyd, but the two biggest influences on him, according to the book written by his wife Pamela, were Jimmy Lucas and Bobby Dalgleish. Jimmy was one of Billy's trainers in the yard who helped him to hone his skills as a welder and a comedian.

Connolly also joined the Territorial Army Reserve unit 15th (Scottish) Battalion, the Parachute Regiment (15 PARA). He later commemorated his experiences in the song "Weekend Soldier".[23]

Career

[edit]Origin of "The Big Yin"

[edit]Connolly's nickname The Big Yin was first used during his adolescent years to differentiate between himself and his father.[2] "My father was a very strong man. Broad and strong. He had an 18+1⁄2-inch [470 mm] neck collar. Huge, like a bull. He was "Big Billy" and I was "Wee Billy". And then I got bigger than him, and the whole thing got out of control. And then I became The Big Yin in Scotland. So, we'd go into the pub and someone would say, 'Billy Connolly was in.' 'Oh? Big Billy or Wee Billy?' 'The Big Yin.' 'Oh, Wee Billy.' If you were a stranger, you'd think, 'What are these people talking about?!'"[24]

1960s

[edit]In the early 1960s, Connolly attended the Edinburgh Festival Fringe for the first time. After spending time on the city's Rose Street, patronising the various drinking establishments, he became enamoured by some long-haired musicians and decided to model himself on them.[25]

In 1965, after he had completed a 5-year apprenticeship as a boilermaker, Connolly accepted a ten-week job building an oil platform in Biafra, Nigeria. Upon his return to the United Kingdom, via Jersey, he worked briefly at John Brown & Company but decided to walk out on a Fair Friday to focus on being a folk singer.

After watching The Beverly Hillbillies, he bought his first banjo at the Barrowland market.[14] He began to tour with the folkie crowd, including regular stints at The Scotia bar, on Stockwell Street, guided by folk singer Danny Kyle. "I kind of introduced Billy to the folk clubs, such as there were in those days – there were very few in those days. We used to go to places like Saturday Late or the Montrose Street Glasgow Folk Club."[18]

Connolly formed a folk-pop duo called the Humblebums with Tam Harvey. In 1969, they were joined by Gerry Rafferty, who had approached Connolly after a gig in Paisley. The band signed for independent label, Transatlantic Records, and after recording one album (1969's First Collection of Merry Melodies), Harvey left the trio and Connolly and Rafferty went on to release two more albums: The New Humblebums (1969) and Open up the Door (1970). Connolly's time with Rafferty possibly influenced his future comedy, because years later he would recall how Rafferty's expert prank telephone calls, made while waiting to go on stage, used to make him "scream" with laughter. Connolly's contributions were primarily straightforward pop-folk with quirky and whimsical lyrics, but he had not especially focused on comedy at this point.

In 1968,[16] a 26-year-old Connolly married Springburn native and interior designer Iris Pressagh, with whom he had two children. They initially lived on Redlands Road in Glasgow's West End, but, when fans began to wait out in the street, they moved to Drymen near the south-eastern shore of Loch Lomond.

Later that year,[16] Connolly's mother went to meet him backstage after a Humblebums gig in Dunoon, where she was working in the cafeteria at Dunoon General Hospital. It was the second and final meeting between them since she had abandoned Connolly.[14] She had been living in the town with her partner, Willie Adams, with whom she had three daughters and a son.[26] "I went home to her house and stayed the night, instead of the hotel. The sadness is... She was a very nice woman, but we never got along. We both tried to like each other, and I don't think she liked me very much. I don't regret it, but I'm sad about it. I wish I'd liked her. And I wish she'd liked me."[16]

In 1971, the Humblebums broke up, with Rafferty going on to record his solo album Can I Have My Money Back? Connolly returned to being a folk singer. His live performances featured humorous introductions that became increasingly long. The head of Transatlantic Records, Nat Joseph, who had signed The Humblebums and had nurtured their career, was concerned that Connolly find a way to develop a distinctive solo career just as his former bandmate, Gerry Rafferty, was doing.[citation needed] Joseph saw several of Connolly's performances and noted his comedic skills. Joseph had nurtured the recording career of another Scottish folk entertainer, Hamish Imlach, and saw potential in Connolly following a similar path. He suggested to Connolly that he drop the folk-singing and focus primarily on becoming a comedian.[citation needed]

1970s

[edit]In 1972, Connolly made his theatrical debut, at the Cottage Theatre in Cumbernauld, with a revue called Connolly's Glasgow Flourish.[7] He played the Edinburgh Festival Fringe with poet Tom Buchan, with whom he had written The Great Northern Welly Boot Show, and in costumes designed by the artist and writer John Byrne, who also designed the covers of the Humblebums' records.[7]

Also in 1972, Nat Joseph produced Connolly's first solo album, Billy Connolly Live!, a mixture of comedic songs and short monologues that hinted at what was to follow. In late 1973, Joseph produced the breakthrough album that propelled Connolly to British stardom. Recorded at a small venue, The Tudor Hotel in Airdrie, the record was a double album titled Solo Concert. Releasing a live double-album by a comedian who was virtually unknown (except to a cult audience in Glasgow) was an unusual gambit by Joseph but his faith in Connolly's talent turned out to be warranted. Joseph and his marketing team, which included publicist Martin Lewis, promoted the album to chart success on its release in 1974. It featured one of Connolly's most famous comedy routines — "The Crucifixion" — in which he likens Christ's Last Supper to a drunken night out in Glasgow. The recording was banned by many radio stations at the time.

In 1974, he sold out the Pavilion Theatre in his home town.[7] In 1975, the rapidity and extent of Connolly's breakthrough was used to secure him a booking on Britain's premier TV chat show, the BBC's Parkinson. Connolly made the most of the opportunity and, ignoring objections from his manager,[7] told a bawdy joke about a man who had murdered his wife and buried her bottom-up so he'd have somewhere to park his bike. This ribald humour was unusually forthright on a primetime Saturday night on British television in the mid-1970s, and his appearance made a great impact. "When I finished that show, I came back to Glasgow, and I was coming through the airport and the whole airport started to applaud."[28] Connolly became a good friend of the host, Michael Parkinson, and now holds the record for appearances on the programme, having been a guest on fifteen occasions.[29] Referring to that debut appearance, he later said: "That programme changed my entire life." Parkinson, in the documentary, Billy Connolly: Erect for 30 Years, stated that people still remember Connolly telling the punchline to the 'bike joke' three decades after that TV appearance. When asked about the material, Connolly stated, "Yes, it was incredibly edgy for its time. My manager, on the way over, warned me not to do it, but it was a great joke and the interview was going so well, I thought, 'Oh, fuck that!!' I don't know where I got the courage in those days, but Michael did put confidence in me."[29] Connolly's success spread to other English-speaking countries: Australia, New Zealand, and Canada. However, his broad Scottish accent and British cultural references made success in the US improbable.

His increased profile led to contact with other celebrities; including musicians such as Elton John. John at that time was trying to assist British performers whom he personally liked to achieve success in the United States (he had released records in the US by veteran British pop singer Cliff Richard on his own Rocket label). John tried to give Connolly a boost in America by using him as the opening act on his 1976 US tour, but the well-intentioned gesture was a failure. John's American fans had no interest in being warmed-up by an unknown comedian – especially a Scotsman whose accent they found incomprehensible. "In Washington, some guy threw a pipe and it hit me right between my eyes", he told Michael Parkinson two years later. "It wasn't my audience. They made me feel about as welcome as a fart in a spacesuit."[30] The quip caused fellow guest Angie Dickinson to laugh uncontrollably.[31]

Connolly continued to grow in popularity in the UK. In 1975, he signed with Polydor Records. Connolly continued to release live albums and he also recorded several comedic songs that enjoyed commercial success as novelty singles including parodies of Tammy Wynette's song "D.I.V.O.R.C.E." (which he performed on Top of the Pops in December 1975) and the Village People's "In the Navy" (titled "In the Brownies").[7]

In 1976, Connolly's first play, An' Me wi' a Bad Leg, Tae, opened in Irvine and toured in London. It was there that, after consuming a sizable amount of cocaine and alcohol, he collapsed on the floor of a recording studio.[7] In 1979, Connolly met Pamela Stephenson, the New Zealand-born comedy actress, for the first time when he made a cameo appearance on the BBC sketch show, Not the Nine O'Clock News, in which she was one of the four regular performers.[7]

Returning to the stage, Connolly embarked on his Big Wee Tour of Britain, performing 69 dates in 84 days. While backstage in Brighton, he met Stephenson for a second time. He confided in her that he was unhappy and that his current marriage was over. Back at his hotel, where they began an affair, he reportedly drank thirty brandies. "What I saw of him – particularly in that dressing room – was that he was about to die," Stephenson said. "He was very suicidal. He was throwing everything away, desperately trying to feel no pain at all. You know how you get a sense from some people when they are very self-destructive that there is something they are trying to bury? They've got something they are trying to forget, or they are trying to drown their sorrows? He was hurting in a very deep way. I thought, 'If I leave this man, he's going to die.'"[7]

Also in 1979, Connolly was invited by producer Martin Lewis to join the cast of The Secret Policeman's Ball, the third in the series of The Secret Policeman's Balls fundraising shows for Amnesty International. Connolly was the first comedic performer in the series who was not an alumnus of the Oxbridge school of middle-class university-educated entertainers and he made the most of his appearance. Appearing in the company of long-established talents such as John Cleese and Peter Cook helped elevate the perception of Connolly as one of Britain's leading comedic talents. Lewis also teamed Connolly with Cleese and Cook to appear in the television commercial for the album.

1980s

[edit]In 1981, John Cleese and Martin Lewis invited Connolly to appear in that year's Amnesty show, The Secret Policeman's Other Ball. The commercial success of the special US version of The Secret Policeman's Other Ball film (Miramax Films, 1982) introduced Connolly to a wider American audience, who were attracted to the film because of the presence of Monty Python members. His on-screen presence alongside these performers – who were already familiar to Anglophile comedy buffs – helped lay down a marker for Connolly's eventual return to the US in his own right eight years later.

En route to begin filming Water (1985) in Saint Lucia, Connolly drank an excessive amount of alcohol on the plane. Upon arriving on the island, he had dinner with the cast and crew, including Michael Caine.

They had a jolly evening, then travelled back by bus through a part of the island that features steep cliffs on either side of a jungle road. As they careered along, Billy thought it would be a wheeze to cover the driver's eyes with his hands. 'I'll guide you,' insisted our drunken control-freak, 'Left, right... more right.' It was a game he had apparently played with his London driver: God knows how they managed to survive. Michael Caine apprehended Billy just in time to save the bus from plunging down a St Lucian ravine.[21]

— Excerpt from Billy by Pamela Stephenson (2001)

In 1985, he divorced Iris Pressagh, his wife of sixteen years (they had separated four years earlier), and he was awarded custody of their children Jamie and Cara.[21][26] That same year, he performed An Audience with..., which was videotaped at the South Bank Television Centre in front of a celebrity audience for ITV. The uncut, uncensored version was subsequently released on video. In July 1985, Connolly performed at Live Aid at Wembley Stadium, immediately preceding Elton John, whom he introduced on stage.[32]

1990s

[edit]Although Connolly had performed in North America as early as the 1970s and had appeared in several movies that played in American theatres, he nonetheless remained relatively unknown until 1990 when he was featured in the HBO special Whoopi Goldberg and Billy Connolly in Performance, produced by New York's Brooklyn Academy of Music. Soon after, Connolly succeeded Howard Hesseman as the star of the sitcom, Head of the Class for its final season. He would also take part on its spin-off series Billy. Connolly joined boxer Frank Bruno and Ozzy Osbourne when singing "The War Song of the Urpneys" in the British animated television series The Dreamstone.[33]

In 1991, HBO released Billy Connolly: Pale Blue Scottish Person, a standup performance recorded at the Wilshire Ebell Theatre in Los Angeles, California.[34]

On 4 June 1992, Connolly performed his 25th-anniversary concert in Glasgow. Parts of the show and its build-up were documented in The South Bank Show, which aired later in the year.[35] In early January 1994, Connolly began a 40-date World Tour of Scotland, which would be broadcast by the BBC later in the year as a six-part series. It was so well received he did Billy Connolly's World Tour of Australia for the BBC in 1995. The eight-part series followed Connolly on his custom-made Harley Davidson trike. Also in 1995, Connolly recorded a BBC special, entitled A Scot in the Arctic, in which he spent a week by himself in the Arctic Circle. He voiced Captain John Smith's shipmate, Ben, in Disney's animated film, Pocahontas.[36]

In 1996, he appeared in Muppet Treasure Island as Billy Bones. In 1997, he starred with Dame Judi Dench in Mrs Brown, in which he played John Brown, the favoured Scottish servant of Queen Victoria. He was nominated for the BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role and a BAFTA Scotland Award for Best Actor, as well as a Screen Actors Guild Award for Best Supporting Actor for his performance.[37]

In 1998, Connolly's best friend, Danny Kyle, died. "He was my dearest, dearest, oldest friend", Connolly explained to an Australian audience on his Greatest Hits compilation, released in 2001. It was Kyle who helped Connolly overcome his habit of recoiling on being touched by others, a remnant of the abuse he endured as a child. "Every time it happened, Danny would just collapse with hysterics," said Pamela Stephenson.[14] "'That's not normal, Billy,' Danny tried to be patient with him. 'You'll have to relax. It's touchy-feely, you know, the way we live. We like to touch each other and we kiss: we're different. You'll have to calm down or you'll always be fighting.'"[14]

He performed a cover version of the Beatles' song, "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite" on George Martin's 1998 album, In My Life. In November 1998, Connolly was the subject of a two-hour retrospective entitled, Billy Connolly: Erect for 30 Years, which included tributes from Dench, Sir Sean Connery, Whoopi Goldberg, Robin Williams, Dustin Hoffman, and Eddie Izzard.[38]

In 1999, after forming Tickety-Boo management company with Malcolm Kingsnorth, his tour manager and sound engineer of 25 years, Connolly undertook a four-month, 59-date sellout tour of Australia and New Zealand. Later in the year, he completed a five-week, 25-date sellout run at London's Hammersmith Apollo.

2000s

[edit]

In 2000, Connolly starred in Beautiful Joe alongside Sharon Stone. The following year, he completed the third in his "World Tour" BBC series, this time of England, Ireland and Wales, which began in Dublin and ended in Plymouth. It was broadcast the following year. Also in 2001, Stephenson's first biography of her husband, Billy, was published. Much of the book is about Connolly the celebrity but the account of his early years provides a context for his humour and point of view. A follow-up, Bravemouth, was published in 2003.

A fourth BBC series, World Tour of New Zealand, was filmed in 2004 and aired that winter. Also in his 63rd year, Connolly performed two sold-out benefit concerts at the Oxford New Theatre in memory of Malcolm Kingsnorth. He has continued to be a much in-demand character actor, appearing in several films such as White Oleander (2002), The Last Samurai (2003), and Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events (2004). He has played an eclectic collection of leading roles in recent years, including a lawyer who undertakes a legal case of Biblical proportions in The Man Who Sued God (2001), and a young boy's pet zombie in Fido (2006).[39]

Also in 2005, Connolly and Stephenson announced, after fourteen years of living in Hollywood, they were returning to live in the former's native land. They purchased a 120-foot (37 m) yacht with the profits from their house-sale and split the year between Malta and the 12-bedroom Candacraig House in Strathdon, Aberdeenshire, which they had purchased in 1998 from Dame Anita Roddick.[39][40]

Later in the year, Connolly topped an unscientific poll of "Britain's Favourite Comedian" conducted by the network Five, placing him ahead of performers such as John Cleese, Ronnie Barker, Dawn French, and Peter Cook. In 2006, he revealed he has a house on the Maltese island of Gozo.[41] He and his wife also have an apartment in New York City near Union Square.[42]

On 30 December 2007, Connolly escaped uninjured from a single-car accident on the A939 near Ballater, Aberdeenshire.[43]

2010s

[edit]In 2011, Connolly and his wife were living full-time in New York City, whilst retaining their Candacraig residence.[44] The Connollys decided to sell Candacraig House in September 2013, with a price of £2.75 million.[39]

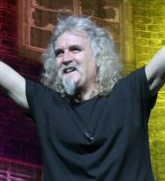

In 2012, Connolly provided the voice of King Fergus in Pixar's Scotland-set animated film Brave, alongside fellow Scottish actors Kelly Macdonald, Craig Ferguson, Robbie Coltrane, Emma Thompson, and Kevin McKidd. Connolly appeared as Wilf in Quartet, a 2012 British comedy-drama film based on the play Quartet by Ronald Harwood, directed by Dustin Hoffman.

In 2014, he appeared in The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies as Dáin II Ironfoot, a great dwarf warrior and cousin of Thorin II Oakenshield. Peter Jackson stated: "We could not think of a more fitting actor to play Dain Ironfoot, the staunchest and toughest of dwarves, than Billy Connolly, the Big Yin himself. With Billy stepping into this role, the cast of The Hobbit is now complete. We can't wait to see him on the battlefield."[45]

Steve Brown, Connolly's manager of 32 years, died in December 2017 at the age of 72.[46] In 2018, Connolly, now resident in Florida, held his first art exhibition. He stated at the time that he would no longer be touring as a comedian.[47]

2020s

[edit]As of 2021, he and his wife live in Florida. He published an autobiography, Windswept and Interesting, in October 2021.[48]

In May 2022, Connolly received a BAFTA Fellowship in celebration of his five-decade long career.[49]

Personal life

[edit]

Connolly married Iris Pressagh in 1969. They separated in 1981 and divorced in 1985. In 1981 he began living with Pamela Stephenson; they were married in Fiji on 20 December 1989.[1] "Marriage to Pam didn't change me; it saved me," he later said. "I was going to die. I was on a downwards spiral and enjoying every second of it. Not only was I dying, but I was looking forward to it."[7] Connolly has two children from his first marriage and three from his second. He became a grandfather in 2001, when his daughter Cara gave birth to Walter.[7]

In 1986, Connolly gave up alcohol, having been a heavy drinker.[50] "I don't miss drinking. It has taken me by surprise," Connolly stated 24 years later.[16] "I miss the craic. I miss the joy of it all. The headbanging stupidity, the loveliness, the craziness of it. I miss it terribly." He recalls blackouts that he would fill in upon returning to sobriety. "Well, [the memories] stopped coming back. But when I drank, I would go, 'Oh, I remember now.'" Connolly is describing the phenomenon of state-dependent learning.[16] "That was frightening. I remember thinking, 'Beware, Billy boy. Beware. All is not well. Do something.'" Regarding the decision he made to stay sober: "If Pamela goes away, I'm on my own. There's nothing. There's only me and it. So the choice becomes very apparent."[16]

Also in 1986, he visited Mozambique to appear in a documentary for Comic Relief. He also featured in the charity's inaugural live stage show, both as a stand-up and portraying a willing "victim" in his partner Pamela Stephenson's act of sawing a man in half to create two dwarfs. Connolly completed his first world tour in 1987, including six nights at the Royal Albert Hall in London, which was documented in the Billy and Albert video. In March 1988, his father died after a stroke, the eighth of his life.[13][21][51] His mother died five years later, in 1993, of motor neurone disease.

"It's up to yourself. You manufacture it [optimism]. You either look at the world one way or another. It's the old half full half empty. It's up to you. The world's a great place, it's full of great people. The choice is yours. [Pessimism] is a luxury you can't afford".

In the book Billy (and in a December 2008 online interview), Connolly states he was sexually abused by his father between the ages of ten and fifteen. He believes this was a result of the Catholic Church not allowing his father to divorce after his mother left the family. Because of this, Connolly has a "deep distrust and dislike of the Catholic church and any other organisation that brainwashes people".[53] He has called himself an atheist.[54]

In September 2013, Connolly underwent minor surgery for early-stage prostate cancer.[55] The announcement also stated that he was being treated for the initial symptoms of Parkinson's disease.[56] Connolly had acknowledged earlier in 2013 that he had started to forget his lines during performances.[57][58] In January 2019, he disclosed that its advance may force his retirement from performing.[59][1]

In 2018, Connolly moved to Key West, Florida.[60][1] He supports Celtic.[61] Connolly has attention deficit disorder.[62]

Ancestry

[edit]Connolly's paternal grandfather, whom—like his paternal grandmother—Connolly never met, was an Irish immigrant who left Ireland when he was ten years old.[63][64][14] His great-great-great-grandfather (Charles Mills, a coast guard, 1796–1870)[65] and great-great-grandfather (Bartholomew Valentine Connolly) were from Connemara.[63]

His father was William Connolly; his mother, Mary "Mamie" McLean, was from the Clan Maclean of Duart Castle on the Isle of Mull on the west coast of Scotland. Mamie's father, Neil, was a Protestant and her mother, Flora, was a Roman Catholic who "made clandestine arrangements for the children to be baptised as Catholics", even though they were "formally raised as Protestants".[63] His maternal grandparents moved inland to Finnieston Street, Glasgow, in the early 1900s.[66]

Connolly appeared on the BBC's genealogy programme Who Do You Think You Are? on 2 October 2014, in which he discovered his Indian ancestry.[67][68] His maternal great-great-great-grandfather, John O'Brien, fought at the Siege of Lucknow during the Indian Rebellion of 1857. He was wounded during the long siege by a severe gunshot to the left shoulder. He married a local 13-year-old Indian girl called Matilda. They had four children and settled in Bangalore after his military service.[67][69]

Political views

[edit]Connolly has been a vocal opponent of Scottish independence. In 1974, he made a political party television broadcast on behalf of the Labour Party which criticised the Scottish National Party. In 1999, he blamed the SNP for a perceived increase in Anglophobia in Scotland; described the new Scottish Parliament as a joke; and declined to attend the opening ceremony.[70]

Connolly questioned the expense of independence, and whether average Scots would benefit from another level of government, though he added "Scots are very capable of making up their mind without my tuppence worth."[71]

In April 2014, in an interview with the Radio Times leading up to the independence referendum, he stated "I think it's time for people to get together, not split apart. The more people stay together, the happier they'll be." He also referred to the Darien scheme, an effort to establish a Scottish colony in the Isthmus of Panama in 1698; the colony's failure destroyed the Kingdom of Scotland's economy and led to the Acts of Union in 1707. Connolly wrote, "You must remember that the Union saved Scotland. Scotland was bankrupt and the English opened us up to their American and Canadian markets, from which we just flowered."

During an interview with the BBC prior to polling day for the Scottish independence referendum on 18 September 2014, Connolly revealed he would not be voting as he was flying to New Zealand that day. He re-iterated his view that the people of Scotland did not need his opinion to make up their minds on the subject.[72]

In October 2018, several media outlets stated that in his book Made in Scotland, released on 10 October, Connolly had voiced his support for independence in light of the 2016 referendum on the United Kingdom leaving the European Union (Brexit), in which Scotland voted to remain. The Times reported Connolly as calling the Brexit vote a "disaster" and saying that independence "may be the way to go" in order for Scotland to maintain a connection to Europe.[73][74] In Episode Five of the BBC Scotland documentary, Billy and Us, first broadcast on 11 June 2020, he said "I've never liked nationalism in any of its guises. I'm not saying I've never agreed with independence. I think a Scottish republic is as good an idea as any I ever heard."[75]

Support for charity

[edit]Connolly is a patron of the National Association for Bikers with a Disability.[76] He is also a patron of Celtic F.C.'s The Celtic Foundation.[77]

Other ventures

[edit]Folk music

[edit]I'll never forget. I was at a Pete Seeger concert in the early 1960s in Glasgow. I'd just bought a banjo. I'd seen him on television and I thought 'That's what I want to do.' He was just exquisitely good. He said, 'I would like to sing a song by a new hero of mine, he's a young man – Bob Dylan.' He sang "A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall". I'm almost crying at the thought. It was sensational. I became another guy: me. He sang, 'I saw a white man; he was walking a black dog,' and I thought, 'This is different.' It changed me forever, in a way I'll be eternally grateful for.[16]

In 1965, together with Tam Harvey, Connolly started a group called the Humblebums. At their first gig, Connolly reportedly introduced them both to the audience by saying, "My name's Billy Connolly, and I'm humble. This is Tam Harvey, he's a bum." The band would later include Gerry Rafferty, who saw Connolly at a charity show in Paisley.[78] "Gerry was very good for me. He taught me that I would never be a musician as long as my arse looked south. He was just so outstandingly good and getting better, and although I was getting better too, the space between us remained huge. He was a real musician, he knew and felt music, a bass player, with a lovely sense of harmony, as well as a great guitarist. I knew tunes and how to play them but that was where my musicianship ended. Unfortunately, I'm still the same to this day. I work very hard, I play every day but I'm still ordinary. I can be flashy, but it's all tricks really. He's a musician and I'm just not in the same league. So, I gave up these ambitions and concentrated on what I was really born to do."[78]

After Harvey left the group, Connolly and Rafferty continued as a duo and the latter two of their three albums featured just that duo. Connolly sang, played five-string banjo, guitar, and autoharp, and at live shows entertained the audience with his humorous introductions to the songs.

Frank Bruno and Connolly provided lead vocals on, "The War Song of the Urpneys" from The Dreamstone; although the version heard in the series was largely sung by composer Mike Batt.

In his World Tour of Scotland, Connolly revealed that, at a trailer show during the Edinburgh Festival, the Humblebums took to the stage just before Yehudi Menuhin.

The Humblebums broke up in 1971 and both Connolly and Rafferty went solo. Connolly's first solo album in 1972, Billy Connolly Live! on Transatlantic Records, featured him as a singer-songwriter.

His early albums were a mixture of comedy performances, with comedic and serious musical interludes. Among his best-known musical performances were "The Welly Boot Song", a parody of the Scottish folk song "The Wark O' the Weavers", which became his theme song for several years; "In the Brownies", a parody of the hit Village People songs "In the Navy" and "Y.M.C.A." (for which Connolly filmed a music video); "Two Little Boys in Blue", a tongue-in-cheek indictment of police brutality done to the tune of Rolf Harris' "Two Little Boys"; and the ballad "I Wish I Was in Glasgow", which Connolly would later perform in duet with Malcolm McDowell on a guest appearance on the 1990s American sitcom Pearl (which starred Rhea Perlman). He also performed the occasional Humblebums-era song such as, "Oh, No!" as well as straightforward covers such as a version of Dolly Parton's "Coat of Many Colors", both of which were included on his Get Right Intae Him! album.

In November 1975, his rendition of Ben Colder's 1969 spoof of the Tammy Wynette song "D-I-V-O-R-C-E" was a UK No. 1 single for one week. Wynette's original was about parents spelling out words of an impending marital split to avoid traumatising their young child. The spoof version centred on dog owners using the same tactic to avoid worrying their pet about an impending trip to the vet (spelling out "W-O-R-M" or "Q-U-A-R-A-N-T-I-N-E", for example). His song, "No Chance" was a parody of J. J. Barrie's cover of the song "No Charge".

In 1985, he sang the theme song to Super Gran which was released as a single. In 1996, he performed a cover of Ralph McTell's "In the Dreamtime" as the theme to his World Tour of Australia. By the late 1980s, Connolly had all but dropped the music from his act, though he still records the occasional musical performance, such as a 1980s recording of his composition "Sergeant, Where's Mine?" with the Dubliners. In 1998, he covered the Beatles' "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!" on the George Martin tribute album In My Life. He sang the Scottish folk song "Bonnie George Campbell" during the film Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events. In 1995 and 2005, he released two albums of instrumental performances, Musical Tour of Scotland and, Billy Connolly's Musical Tour of New Zealand, respectively.

Connolly is among the artists featured on Banjoman, a tribute to American folk musician Derroll Adams, released in 2002. He played one song, "The Rock".

Stand-up comedy

[edit]

Connolly's observational comedy is idiosyncratic and often off-the-cuff. He has offended certain sectors of audiences, critics and the media with his free use of the word "fuck", and he has made jokes relating to masturbation, blasphemy, defecation, flatulence, hemorrhoids, sex, his father's illness, his aunts' cruelty and, in the latter stages of his career, old age (specifically his experiences of growing old).[79]

In 2007 and again in 2010, he was voted the greatest stand-up comic on Channel 4's 100 Greatest Stand-Ups.[80] He once again topped the list on Channel 5's Greatest Stand-Up Comedians, broadcast on New Year's Eve 2013.[81]

Since the 1980s, Connolly has worn a custom-made black T-shirt with a shirt-tail as part of his on-stage attire. Steve Brown was his manager from 1986 until his death in 2017.[82]

Comics writing

[edit]Between 1973 and 1977, Connolly wrote a newspaper gag-a-day comic with cartoonist Malky McCormick, titled The Big Yin.[83]

Art

[edit]Connolly has published eleven collections of his art.[84] His method is similar to that of the Surrealist Automatism movement, whereby the artist allows their hand to move randomly across the paper or canvas without a specific intent. In April 2019, to celebrate World Parkinson's Day, his art was projected onto MacLellan's Castle in Kirkcudbright.[85] His first sculpture, which is inspired by his past as a welder, was released in March 2020.[86] He spoke about his art and the inspiration behind it on the occasion of his 80th birthday in 2022.[87]

Discography

[edit]Below is a partial list of Connolly's solo musical and comedic recordings. For his releases with the Humblebums, see here.

- 1972 – Billy Connolly Live

- 1974 – Cop Yer Whack for This

- 1974 – Solo Concert

- 1975 – Get Right Intae Him! (#80 AUS[88])

- 1975 – Words and Music

- 1975 – The Big Yin

- 1976 – Atlantic Bridge

- 1977 – Billy Connolly

- 1977 – Raw Meat for the Balcony!

- 1978 – Anthology

- 1979 – Riotous Assembly

- 1981 – The Pick of Billy Connolly (compilation) (#34 AUS[88])

- 1983 – A Change Is as Good as Arrest

- 1983 – In Concert

- 1984 – Big Yin Double Helping (compilation)

- 1985 – An Audience with Billy Connolly

- 1985 – Wreck on Tour

- 1987 – Billy & Albert

- 1991 – Live at the Odeon Hammersmith London

- 1995 – Musical Tour of Scotland

- 1995 – Live DownUnder 1995 (#23 AUS[89])

- 1996 – World Tour of Australia

- 1997 – Two Night Stand

- 1999 – Comedy and Songs (compilation)

- 1999 – One Night Stand Down Under

- 2002 – Live in Dublin 2002

- 2002 – The Big Yin – Billy Connolly in Concert (compilation)

- 2003 – Transatlantic Years (compilation of material recorded between 1969 and 1974)

- 2003 – Humble Beginnings: The Complete Transatlantic Recordings 1969–74

- 2005 – Billy Connolly's Musical Tour of New Zealand

- 2007 – Live in Concert

- 2010 – The Man: Live in London (recorded January 2010)

- 2011 – Billy Connolly's Route 66

VHS / DVD releases

[edit]| Year | Title |

|---|---|

| 1981 | Bites Yer Bum |

| 1982 | The Pick of Billy Connolly |

| 1985 | An Audience with Billy Connolly |

| 1987 | Billy and Albert – Live at the Royal Albert Hall |

| 1991 | Live at the Odeon Hammersmith |

| 1992 | The Best of 25 Years of Billy Connolly (25BC) |

| 1994 | Live 1994 |

| 1995 | Two Bites of Billy Connolly |

| 1997 | Two Night Stand – Live From London and Glasgow |

| 1998 | Erect for 30 Years |

| 1999 | Live 99 – One Night Stand Down Under and The Best of the Rest |

| 2001 | Live – The Greatest Hits |

| 2002 | Live in Dublin 2002 |

| 2005 | Live in New York |

| 2006 | The Essential Collection |

| 2007 | Was It Something I Said? |

| 2010 | Live in London 2010 |

| 2011 | You Asked For It |

| 2016 | High Horse Tour Live |

Playwright

[edit]Connolly has written three plays:

- An' Me Wi' A Bad Leg Tae (1975)

- When Hair Was Long And Time Was Short (1977)

- Red Runner (1979)

Filmography

[edit]Film

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1978 | Absolution | Blakey | |

| 1983 | Bullshot | Hawkeye McGillicuddy | |

| 1985 | Water | Delgado | |

| 1989 | The Return of the Musketeers | Caddie | |

| 1990 | The Big Man | Frankie | |

| 1993 | Indecent Proposal | Auction M.C. | |

| 1995 | Pocahontas | Ben | Voice[90] |

| 1996 | Muppet Treasure Island | Billy Bones | |

| 1997 | Beverly Hills Ninja | Japanese Antique Shop Proprietor | Uncredited |

| Mrs Brown | John Brown | ||

| Paws | PC | Voice[90] | |

| 1998 | The Impostors | Mr. Sparks, the Tennis Pro | |

| Middleton's Changeling | Alibius | ||

| 1999 | Still Crazy | Hughie Case | |

| The Debt Collector | Nicky Dryden | ||

| The Boondock Saints | Noah MacManus / Il Duce | ||

| 2000 | Beautiful Joe | Joe | |

| An Everlasting Piece | Scalper | ||

| 2001 | Gabriel & Me | Gabriel | |

| Who Is Cletis Tout? | Dr. Mike Savian | ||

| The Man Who Sued God | Steve Myers | ||

| 2002 | White Oleander | Barry Kolker | |

| 2003 | Timeline | Professor Johnston | |

| The Last Samurai | Sergeant Zebulon Gant | ||

| 2004 | Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events | Dr. Montgomery "Monty" Montgomery | |

| 2006 | Garfield: A Tail of Two Kitties | Lord Dargis | |

| Fido | Fido | ||

| Open Season | McSquizzy | Voice[90] | |

| 2008 | The X-Files: I Want to Believe | Joseph "Father Joe" Crissman | |

| Open Season 2 | McSquizzy | Voice[90] | |

| 2009 | The Boondock Saints II: All Saints Day | Noah MacManus / Il Duce | |

| 2010 | Gulliver's Travels | King Theodore | |

| 2011 | The Ballad of Nessie | Narrator | Voice |

| 2012 | Brave | King Fergus[90] | |

| Quartet | Wilf Bond | ||

| 2014 | What We Did on Our Holiday | Gordie McLeod | |

| The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies | Dáin II Ironfoot | ||

| 2016 | Wild Oats | Lacey Chandler | [91] |

Television

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1975–1976 | Play for Today | Paddy / Jody | Episodes: "Just Another Saturday" and "The Elephants' Graveyard" |

| 1980 | Not the Nine O'Clock News | Various roles | 2 episodes |

| Worzel Gummidge | Bogle McNeep | Episode: "A Cup 'O Tea and a Slice 'O Cake" | |

| 1980–1981 | The Kenny Everett Video Cassette | Various roles | 3 episodes |

| 1982–1983 | The Kenny Everett Television Show | 9 episodes | |

| 1983 | Androcles and the Lion | Androcles | Television film |

| 1984–1985 | Tickle on the Tum | Bobby Binns | 2 episodes |

| 1985–1987 | Super Gran | Angus McSporran | Episode: "Supergran and the Course of True Love"; also theme composer |

| 1985 | Blue Money | Des | Television film |

| 1988 | City Lights | The Dosser | Episode: "It's a Wonderful Life, Too" |

| Minder | Tick Tack | Episode: "Fatal Impression" | |

| 1991 | Screen Two | Game Show Host / Busker | Episode: "Dreaming" |

| 1990–1991 | Head of the Class | Billy MacGregor | 22 episodes |

| 1992 | Billy | 13 episodes | |

| 1993 | Screen One | Jo Jo Donnelly | Episode: "Down Among the Big Boys" |

| 1994 | World Tour of Scotland | Himself (host) | 6 episodes |

| 1995 | A Scot in the Arctic | Television special | |

| 1996 | Dennis the Menace and Gnasher | Captain Trout | Voice Episode: "Dennis Ahoy!" |

| 1996 | Billy Connolly's World Tour of Australia | Himself (host) | 8 episodes |

| 1996–1997 | Pearl | William 'Billy' Pynchon | 2 episodes |

| 1997 | Deacon Brodie | William Brodie | Screen One Special |

| 1998 | Veronica's Closet | Campbell | Episode: "Veronica's Got A Secret" |

| Tracey Takes On... | Rory Cassidy | Episode: "Culture" | |

| 1999 | 3rd Rock from the Sun | Inspector Macaffery | Episode: "Dial M for Dick" |

| 2001 | Columbo | Findlay Crawford | Episode: "Murder with Too Many Notes " |

| Prince Charming | Hamish | Television film | |

| Gentlemen's Relish | Kingdom Swann | ||

| 2002 | Billy Connolly's World Tour of England, Ireland and Wales | Himself (host) | 8 episodes |

| 2004 | Billy Connolly's World Tour of New Zealand | ||

| 2009 | Billy Connolly: Journey to the Edge of the World | 4 episodes | |

| 2011 | Billy Connolly's Route 66 | ||

| 2012 | House | Thomas Bell | Episode: "Love is Blind" |

| 2014 | Billy Connolly's Big Send Off | Himself (host) | 2 episodes |

| 2016 | Billy Connolly's Tracks Across America | 3 episodes | |

| Judi Dench: All the World's Her Stage | Himself | BBC documentary about Judi Dench | |

| 2017 | Billy Connolly & Me: A Celebration | Television documentary | |

| Billy Connolly: Portrait of a Lifetime | |||

| 2018 | Billy Connolly's Ultimate World Tour | Himself (host) | 1 episode |

| 2019 | Billy Connolly: Made in Scotland | Himself | 2 episodes |

| Billy Connolly's Great American Trail | Himself (host) | 3 episodes | |

| 2020 | Billy and Us | 6 episodes | |

| Billy Connolly: It's Been A Pleasure | Himself | Television documentary | |

| 2021 | Billy Connolly: My Absolute Pleasure | ||

| 2022 | Billy Connolly Does... | Television documentary series[92] | |

| 2024 | In My Own Words | Television documentary series, 1 episode |

Awards and nominations

[edit]- On 11 July 2001, Connolly was awarded an honorary Doctor of Letters (D.Litt.) degree by the University of Glasgow.[93]

- In 2002, the BAFTA presented him with a Lifetime Achievement Award.[94]

- In the 2003 Birthday Honours, Connolly was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE), for "services to Entertainment".[95]

- On 4 July 2006, Connolly was awarded an honorary doctorate by Glasgow's Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama (RSAMD), for his service to performing arts.[96]

- On 18 March 2007 and again on 11 April 2010, Connolly was named Number One in Channel 4's "100 Greatest Stand-Ups".[97]

- On 22 July 2010, Connolly was awarded an honorary degree of Doctor of Letters (D.Litt.) by Nottingham Trent University.[98]

- On 20 August 2010, Connolly was made a Freeman of Glasgow, with the award of the Freedom of the City of Glasgow.[99]

- On 10 December 2012, Connolly picked up his BAFTA Scotland Award for Outstanding Achievement in Television and Film at his BAFTA, A Life in Pictures, interview in the Old Fruitmarket, Glasgow.[100]

- In January 2016, he was presented with the Special Recognition award at the National Television Awards to honour his career.[101]

- In the 2017 Birthday Honours, Connolly was made a Knight Bachelor for "services to entertainment and charity".[102]

- As of 2017, Glasgow has at least three large-scale gable murals commissioned by BBC Scotland and one metalwork mural commissioned by Sanctuary Scotland Housing Association depicting him.[103]

- On 22 June 2017, Connolly received the Honorary degree of Doctor of the University (D.Univ) from University of Strathclyde in Glasgow.[104][105]

- In November 2019, The Glasgow Times named Connolly as The Greatest Glaswegian as determined by a public poll.[106]

- At the BAFTA TV awards of 2022, Connolly was awarded the BAFTA Fellowship.[107]

Bibliography

[edit]- Connolly, Billy; Campbell, Duncan (19 March 1976). Billy Connolly, The Authorized Version. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-330-24767-2.

- Connolly, Billy (27 October 1983). Gullible's Travels. Arrow Books. ISBN 978-0-09-932310-5.

- Connolly, Billy (18 October 2018). Made in Scotland: My Grand Adventures in a Wee Country. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1-78594-370-6.

- Connolly, Billy (17 September 2020). Tall Tales and Wee Stories. Two Roads. ISBN 978-1529361360.

- Connolly, Billy (12 October 2021). Windswept and Interesting (autobiography). Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 978-1-52931-826-5.

- Margolis, Jonathan (5 October 1998). The Big Yin: The Life and Times of Billy Connolly. Orion. ISBN 978-0-7528-1722-4.

- Stephenson, Pamela (2003). Billy. Perennial Currents. ISBN 978-0-06-053731-9.

- Stephenson, Pamela (2002). Billy (Audio Edition read by Pamela Stephenson). HighBridge Company. ISBN 978-1-56511-725-9.

- Stephenson, Pamela (2003). Bravemouth: Living with Billy Connolly. Headline. ISBN 978-0-7553-1284-9.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Stephenson Connolly, Pamela Stephenson (30 September 2023). "Billy Connolly's most intimate interview yet (by his wife): 'Comedians never used to worry about what was correct to say. You said it, and soon found out". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- ^ a b c Stephenson, Pamela (2001). Billy. London, UK: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-711091-9.

- ^ "Billy Connolly 'most influential comedian of all time'". BBC News. 30 January 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ "Billy Connolly is best ever stand-up comedian, say Digital Spy readers". Digital Spy. 17 November 2011. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ "Episode 1.1 The 100 Greatest Stand-Ups 2007". Comedy.co.uk. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "Billy Connolly retains top spot in C4 poll". Comedy.co.uk. 11 April 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "The story of Billy Connolly in 11 and a half chapters". The Herald. 21 September 2009. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums (19th ed.). London: Guinness World Records Limited. p. 320. ISBN 1-904994-10-5.

- ^ "Billy Connolly announces retirement from live performance". The Guardian. 3 December 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ Stanford, Peter (11 March 2020). "Billy Connolly: 'My art is about revealing myself – like being a flasher in a park'". The Telegraph. Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ Sulway, Verity (28 December 2020). "'Happy' Billy Connolly says he's made peace with death as Parkinson's advances". mirror. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ^ a b c Billy Connolly profile. CNN. 16 July 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

I was born at 69 Dover Street.... and I was born apparently on the kitchen floor at 6 o'clock in the evening.

- ^ a b c d e Connolly, Billy (1994). World Tour of Scotland.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Ferguson, Brian (27 September 2017). "Billy Connolly inducted into Scottish music 'hall of fame'". The Observer. Edinburgh, UK. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ "Billy Connolly – Who Do You Think You Are – A tale of far distant exploits of the ancestors of one of Britain's best loved comedians..." The Genealogist. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Billy Connolly". Shrink Rap. 14 August 2009.

- ^ Live in New York DVD

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bragg, Melvin (host) (4 October 1992). "Billy Connolly". The South Bank Show. Season 16. Episode 1. LWT.

- ^ Connolly, Billy (2018). Made in Scotland. United Kingdom: BBC Books. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-78594-373-7.

- ^ "Billy Connolly reveals childhood abuse". BBC News. 23 September 2001. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d Stephenson, Pamela (7 October 2001). "Billy Connolly: The Glory Years". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ Stephenson, Pamela (27 November 2012). Billy. ABRAMS. ISBN 978-1-4683-0379-7 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d Transatlantic Years liner notes

- ^ a b Billy Connolly's World Tour of Australia, 1996

- ^ Billy & Albert DVD, 1987

- ^ a b Adams, Tim (23 September 2001). "Billy Connolly: The interview – Connolly on the couch". The Observer. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "Glasgow Museums: Highlights at People's Palace". Glasgowlife.org.uk. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Billy Connolly: Portrait of a Lifetime (BR Docs)". YouTube. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019.

- ^ a b Radio Times 15–21 December 2007: Goodnight... and Thank You

- ^ Billy Connolly's best bits: The Big Yin's greatest TV lines, Daily Record, 18 April 2017

- ^ The Full Parky, Irish Times, 10 January 1998

- ^ Hillmore, Peter (1985). The Greatest Show on Earth Live Aid. Sidgwick & Jackson. p. 136.

- ^ "The War Song of the Urpneys". Last FM. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ "Billy Connolly: Pale Blue Scottish Person (TV Special 1991)". IMDb. 14 September 1991.

- ^ "The South Bank Show episode guide". TV.com. 4 October 1992. Archived from the original on 17 June 2008. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Pocahontas Cast & Crew". Radio Times. Archived from the original on 9 October 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ "Billy Connolly to Receive BAFTA in Scotland Honour". BAFTA. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ "Billy Connolly: Erect for 30 Years". BBFC. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ a b c McGinty, Stephen (2 September 2013). "Billy Connolly selling his £3m Scottish house". The Scotsman. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Connolly sells Hollywood home to live the good life in Scotland". The Scotsman. 6 October 2005. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ The Late Late Show with Craig Ferguson, 28 September 2006.

- ^ The Late Late Show with Craig Ferguson, 2 November 2009.

- ^ "Billy Connolly in car accident, unhurt". United Press International. 31 December 2007. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ Walsh, John (16 December 2012). "Yin and Yang: How Billy Connolly calmed down (just don't mention Piers Morgan!)". The Independent. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "Connolly to play Hobbit great dwarf". Stuff.co.nz. 9 February 2012. Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ Bryant, Corrina (22 January 2018). "Steve Brown obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "Sir Billy Connolly says 'art is my life now' as he unveils new show". BBC News. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "Sir Billy Connolly: A windswept and interesting life". Radio New Zealand. 9 October 2021.

- ^ "Highest Bafta honour for Sir Billy Connolly". BBC News. 3 May 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ "Billy Connolly". Chortle. Archived from the original on 15 August 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- ^ Ward, Victoria (14 December 2012). "Elderly should be cared for by their children, Billy Connolly says". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "Sir Billy Connolly". Radio 5 Headliners (Podcast). BBC Radio Five Live. 17 October 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2024.

- ^ "Scots 'anti-English' – survey". BBC News. 28 June 1999. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ Lipworth, Elaine (1 August 2008). "No laughing matter". Irish Independent. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

Connolly has tackled drama before, notably in the film Mrs Brown, with Dame Judi Dench, but he's never portrayed anyone like Father Joe, who is psychic and possibly deranged. "I was brought up as a Catholic," Connolly says. "Aye, I have a cousin who is a nun and another cousin who is a missionary priest in Pakistan." He pauses and smiles. "And I am an atheist".

- ^ "Billy Connolly has cancer surgery". BBC News. 16 September 2013. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ Crawley, Jennifer (28 February 2014). "Launceston surgeon Gary Fettke diagnoses Billy Connolly's Parkinson's in hotel lobby encounter". The Mercury. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ^ "Billy Connolly Diagnosed With Parkinson's". Sky News. 16 September 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ^ Sherwin, Adam (16 September 2013). "Billy Connolly undergoes prostate cancer surgery and is diagnosed with Parkinson's – but will keep working". The Independent. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ^ "Billy Connolly confronts his losing battle with Parkinson's disease". Newshub. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ Walker, Lauren (6 October 2019). "Sir Billy Connolly's local Florida store stocks up on Scottish treats". The Scotsman. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ Jenkins, Carla (11 July 2021). "Billy Connolly spotted wearing Celtic face mask on Florida shopping trip". GlasgowLive. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ Kellaway, Lucy (21 December 2012). "Lucy Kellaway talks to Billy Connolly". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 26 April 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

Stephenson's interpretation of Connolly is not always flattering: I read something recently in which she said he was slightly autistic as well as suffering from an attention deficit disorder. "Did she?" He laughs fondly. "She'll accuse me of anything. I don't think I'm autistic, but I do have attention deficit disorder."

- ^ a b c Billy Connolly's World Tour of England, Ireland and Wales, 2002.

- ^ "Billy Connolly Biography". FilmReference.com. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ Willoughby, Roger (2 May 2011). "Charles Mills (c1795-1870) at Bayleek etc". Coastguards of Yesteryear Forum. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ Billy Connolly: Live in London 2010.

- ^ a b Simons, Jake Wallis (2 October 2014). "Who Do You Think You Are? Billy Connolly, review: 'life-affirming'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "TV review: Billy Connolly traces his exotic family tree". The Herald. 2 October 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "Billy Connolly – Who Do You Think You Are – A tale of far distant exploits of the ancestors of one of Britain's best loved comedians..." The Genealogist. 2 October 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "Nationalists dismiss comedian's attack on them over anti-English racism as absurd and nonsense Connolly faces SNP's wrath". The Herald. 28 June 1999. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ^ Brown, Craig (12 December 2012). "Billy Connolly: My mouth's shut on Scottish independence". The Scotsman. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ Cramb, Auslan (29 April 2014). "Billy Connolly risks wrath of pro-independence activists as he admits he 'dislikes patriots'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ Allardyce, Jason (21 October 2018). "Billy Connolly's big Brexit Scotland U-turn". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "Billy Connolly: Scottish Independence may be the way to go after Brexit disaster". Evening Times. 21 October 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "Billy Connolly hits out at 'pathetic' Scottish Labour politicians, by Laura Webster". Glasgow Times. 11 June 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ "NABD Patrons". NABD.org.uk. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "The Celtic Foundation Overview". Celticfc.net. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ^ a b "Billy's Thoughts". Billy Connolly official website. 26 November 2009. Archived from the original on 2 September 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ "BBC Two – Billy Connolly: Made in Scotland, Series 1, Episode 1". BBC. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ "Billy Connolly retains top spot in C4 poll". British Comedy Guide. 11 April 2010. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ "Greatest Stand Up Comedians". Comedy.co.uk. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ Bryant, Corrina (22 January 2018). "Steve Brown obituary". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ "Malky McCormick". Lambiek.net. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ "About Billy Connolly | Castle Fine Art". www.castlefineart.com. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "Billy Connolly lights up Kirkcudbright for Parkinson's". DGWGO. 23 May 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ Billy Connolly | And On Monday, God Made The World, 2 October 2020, retrieved 30 August 2023

- ^ "To celebrate his 80th birthday on November 24, Billy Connolly chatted to Clair Woodward". The Oldie. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ a b Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 72. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ Ryan, Gavin (2011). Australia's Music Charts 1988–2010 (PDF ed.). Mt Martha, Victoria, Australia: Moonlight Publishing. p. 65.

- ^ a b c d e "Billy Connolly (visual voices guide)". Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved 29 September 2024. A green check mark indicates that a role has been confirmed using a screenshot (or collage of screenshots) of a title's list of voice actors and their respective characters found in its credits or other reliable sources of information.

- ^ Fleming, Mike (11 June 2014). "Shirley MacLaine Joins Wild Oats". Deadline. Retrieved 29 September 2024.

- ^ "Billy Connolly Does... a brand-new series for Gold". uktv.co.uk. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "Billy Connolly receives arts honour". BBC News. 11 July 2001. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "Special Award in 2002". BAFTA. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "No. 56963". The London Gazette (1st supplement). 14 June 2003. p. 8.

- ^ "Big Yin awarded honorary degree". BBC News. 4 July 2006. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ "100 Greatest Stand-Ups". Channel 4. Archived from the original on 4 October 2009. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Stars of stage and screen among honorary graduates of Nottingham Trent University". Nottingham Trent University. 22 July 2010. Archived from the original on 27 August 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ MacNeil, Jason (20 August 2010). "Connolly stays away from patterns". Calgary Sun. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ "Billy Connolly: A Life in Pictures". BAFTA. 18 December 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ "Billy Connolly to receive Special Recognition Award at National Television Awards". The Daily Telegraph. 8 January 2016. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ "No. 61962". The London Gazette (1st supplement). 17 June 2017. p. B2.

- ^ Discovered, Glasgow (30 October 2019). "Billy Connolly | Glasgow History through Street Art". Glasgow Discovered | Showcasing Independent Music and Arts. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ O'Toole, Emer (22 June 2017). "Sir Billy Connolly to receive honorary degree from University of Strathclyde". The Sunday Post. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ "Big Yin becomes honorary doctor". The University of Strathclyde. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "The Big Yin named Greatest Glaswegian by Evening Times readers". Evening Times. 4 November 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "Highest Bafta honour for Sir Billy Connolly". BBC News. 3 May 2022. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

External links

[edit]- Billy Connolly

- 1942 births

- Living people

- 20th-century Scottish comedians

- 20th-century Scottish male actors

- 20th-century Scottish male singers

- 21st-century Scottish comedians

- 21st-century Scottish male actors

- 21st-century Scottish male singers

- 20th-century Scottish dramatists and playwrights

- 21st-century Scottish memoirists

- Acoustic guitarists

- Actors awarded knighthoods

- Audiobook narrators

- British autoharp players

- British boilermakers

- British harmonica players

- British Parachute Regiment soldiers

- Comedians from Glasgow

- Commanders of the Order of the British Empire

- British critics of religions

- Critics of the Catholic Church

- Disney people

- Former Roman Catholics

- Knights Bachelor

- Male actors from Glasgow

- People from Anderston

- People with Parkinson's disease

- People with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- Scottish people with disabilities

- British actors with disabilities

- British musicians with disabilities

- British artists with disabilities

- Polydor Records artists

- Scottish artists

- Scottish atheists

- Scottish banjoists

- Scottish comics writers

- Scottish expatriate male actors in the United States

- Scottish folk singers

- 21st-century Scottish autobiographers

- Scottish male comedians

- Scottish male film actors

- Scottish male guitarists

- Scottish male television actors

- Scottish male voice actors

- Scottish people of Indian descent

- Scottish people of Irish descent

- Scottish stand-up comedians

- Transatlantic Records artists

- Virgin Records artists

- People associated with Nottingham Trent University

- The Humblebums members

- People from Strathdon

- BAFTA fellows